WITH THE SOUND IN YOUR EARS

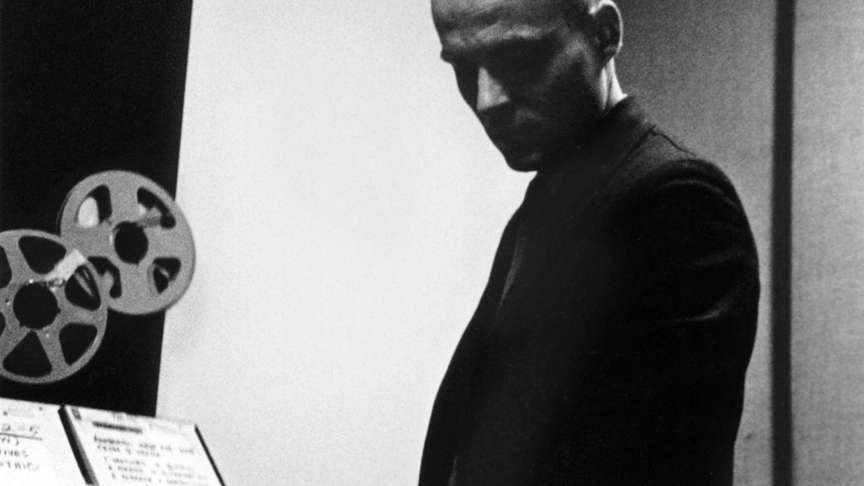

On Tod Dockstader

No one is responsible for an emergence; no one can glory in it, since it always occurs in the interstice

[Feed-forward]

We can maybe begin with history but to historify is to set precedents and conform to the unspoken rules that say there has got to be a first and that then there’s a lineage to follow. So there is genre and the sound of silence and our enthusiasm becomes muted behind a self-perceived lack of knowledge that is always uttered by experts. We are disqualified by history. However, to be self-consciously working in ‘history’ is to be nothing other than to be too closely affixed to the demands and expectations of the present. Instead of this instant contemporaneity, an infamy that is often mediated and emphatically ‘new’, sound-mavericks like Dockstader, following a laborious and singular vein of experimentation, seem to fall into a space that is neither musical nor traditional, neither past nor present.

Listening to Dockstader is like listening to an event as it unfolds for the first time. It is not to eavesdrop on a institutionalised and monologic music of the past, but it is to embrace a form of musical polyphony that does not reduce the “diversity of time” to the hierarchic dimension of originators and imitators. With Dockstader we are invited to listen to sound as it emerges in its materiality: a present becoming the future by way of the past. A reclaimed history. Most of all, as listeners, Dockstader makes sure that we are eminently qualified in that the basis of his experimentation is the basis of our own experimentation as listeners: we too work “directly with the sound” in our ears.Listening is time regained.

[Back-track]

The extent of Dockstader’s experimentation with sound can be gauged by the fact that in the early 60s, when much of his work was ‘constructed’, there was no instant means of categorising such work. This was made more the case by Dockstader’s straddling of the popular and high art cultural zones: working on the production of cartoons and sound-effects whilst scoring a Fellini film and having his pieces played alongside those of Varèse. Yet, in the mid 60s such ‘musique concrete’ experiments were more or less a very fragmentary and dispersed form a minor subset of avant-garde classical music. The centre of gravity may have been Schaeffer’s Groupe de Recherche Musicales and there may have been other nodal points like John Cage’s Fontana Mix and Steve Reich’s Come Out, but what seems to be inflected in Dockstader’s work, like that of Varèse, is just this sense of isolation and difference from the ‘canon’ of electronic music as it was becoming conscious of itself and establishing its paradigms.

Just as Varèse transformed the common conception of the orchestra, pulling it towards a liberation of timbre and rhythm, Dockstader’s tape-splice music, by making ‘noise’ multifariously rich and organising it into highly spatialised compositions, not only insulates itself from being seen as a historic novelty, but presences its ‘process’ approach as running concomitant with the listener’s own exploration of the sounds. Dockstader makes ‘process’ audible as that which actively resists becoming identified as the canon. To echo Morton Feldman, Dockstader’s approach is a case of “vibrant musicality rather than musicianship” and this lack of a self-conscious aspiration to create a music of the canon is audible in Dockstader as the setting free of sounds rather than their being marked by the personality of the ‘composer’ or the ‘musician’.

To say it is an idiosyncratic approach, one that multiplies the points of difference between categories, making the boundaries fuzzy, is something of an understatement. Dockstader’s obsessive means of composition forms a direct link to the obsession of listening where a sense of focus and heightened attention is intimately operative. There is a sense of rapture induced by detail and an infusion of common objects with a poetic resonance that outstrip their ‘real use’. Thus Dockstader’s inclusion of such common objects as balloons and water as source-sounds for his pieces becomes translated into a sense of listeners not only being freed from traditional notions of ‘instruments’ and ‘composers’, but also their being given the option to hear music everywhere. Dockstader thus implies that music should be able to be constructed from any elements and, as with punk, needs only to be fuelled by the desire to express.

Thus we listen on Dockstader’s terms, terms that our own in that they are premised by a more egalitarian ethos than that which attends on a normative classical tradition: the institutionalisation of reception. Dockstader, in succeeding to liberate himself from the need to make music via notation or by access to an orchestra and the sense of ‘schooling’ that this implies, by using and transforming such objects as balloons, brings the production of music much closer to those very listeners who would formerly be seen, condescendingly, as the ‘audience’. His is a music on the interstices of time. On the interstices of expectation. On the interstice of listener and producer.

[Sound-off]

However what informs Dockstader’s (dis)positioning in relation to the classical tradition and even to that of ‘musique concrete’ is the sense that he is not afraid of creating pieces of music that can at times function in a more popular register. This is not to offer such work as Travelling Music as pop music, but it is, in using the hindsight of the techno of the 80s and the electronica of the 90s, to read Dockstader backwards: to listen to his pieces as if they had just occurred. When we do this we not only come face-to-face with the ‘engineer as musician’ but when we contrast the cleanliness of digitalised technology to the timbre-mix in Dockstader’s work (enhanced by his composed use of the spatial dimension of music) we come across a further use of sound as singularised rather than as preset or mass-produced.

Whereas the popularisation of electronic music through techno has prepared us to dispense with notions of ‘acoustic’ being read as ‘authentic’ and where we may be accustomed to the use of sub-bass (cf. Luna Park) what we are not prepared for is Dockstader’s creation of electronic timbres out of almost nothing. Not having access to synthesisers what Dockstader achieves is the building of his own ‘personalised’ synthesiser by the merging of tone generators with found and transformed sounds and then composing his pieces directly onto tape. Another divergence from techno-orthodoxy is that there is an improvisatory feel to Dockstader’s pieces: “moving around, working with your hands, sometimes very fast, more often very slowly… it had a muscular joy… teetering between control and chaos, trying to push the sound a little father forward”.

Dockstader compares his working methods to those he employed in his early years as a painter and what comes across, what gives the music this sense of immediacy and emergence, is just this ‘live’ quality of the pieces where, as with improvised music, there is the imbrication of form and content: a precarious balance between organising the sound and letting the sound disorganise the composition. Thus, through all parts of the process it is as if the intensity of Dockstader’s pieces are a direct outcome of the lack of any mediating device between the sounds, his listening into them and the finished piece we listen into. No screen. No software. No baton. No score. Sounds are neither softened nor made palatable, they are not organised into compositions that make the sounds operate figuratively, but are composed in a way that makes sound audible as a non-narrative process.

Apocalypse (Part 2) with its use of ‘various doors’ and a ‘Gregorian chant’ seems to depict Dockstader in the process of doing everything possible to continually transform his source. This reflexive technique thus raises a use of repetition and it is this aspect that could be seen as another way that his music is different from the traditional approach of musique-concrete. Pieces such as Apocalypse and Quatermass both use the same sources repeatedly and in so doing they inflect the music, not with a repetitious edge, but with a cinematic atmosphere that is creative of a sustained and portentous mood. The Tango piece (and others from Quatermass) also use steady rhythms more readily than other musique concrete electronic/tape constructions. This is also audible during Drone where a repeating bass motif is briefly held-out to feed-forward towards a moment of meta-funk. Once more this points to an appreciation of Dockstader from the vantage point of a more populist approach the 60s pop producer Joe Meek, though intent on record sales, was similarly involved in the possibilities of the music studio and his I Hear A New World concept album bears some resemblance to the more architectonic and finely detailed work of Dockstader. But Meek was mainly interested in enhancing the sound of ballad-singers and beat-groups and did not resist “forcing the sounds too far into music”.

So whilst both Meek and Dockstader both used tape-phasing techniques to create a 3-D effect through echo it is with Dockstader that sound-processing comes to the fore. Sound for sound. Sound as desire. Desire in perception. A group of singular emergences.

[Time-out]

And so listening to Dockstader’s music is like listening to a ‘gap of deferred time’ in that what we hear is neither history nor cult but a sense of our discontinuity from the so-called continuities of musical tradition. That Dockstader’s experiments had to cease because of his “lack of academic credentials” may have had the bonus effect of burying and preserving his work, making it seem like an unintentioned accident that, not being ‘overcoded’ and allotted its place in ‘musical knowledge’, is thus always open to rediscovery by any that stumble across it. Thus it is a music that is always liable to retain something of the vitality and passion that was initially injected into it. For what is communicated in the work of Dockstader is the sense that conformity to categories and expectations is a way to diminish our desire to listen and thereby to repress the continual process of singularisation as it remakes itself through the obsessive pursuit of sounds in transformation.

This is the music of the interstice ... Late nights in a studio in 1961 ... Nothing telling us how to respond...